Discovering the First Network of Maintained Trails in the U.S.

Climbing mountains is somewhat of a silly concept when you really break it down. Hiking as we know it today is a great way to get outside, connect with nature, disconnect from reality, and get a workout in all at once. However, long before it was a pastime, climbing mountains was a way to get from point A to point B. Trails connected towns over mountain passes making for some rugged daily commutes, but the lifestyle bred a group of hardy hikers. These people eventually began clearing trails to high peaks and past natural features, creating the first network of maintained trails in the United States in Waterville Valley, NH.

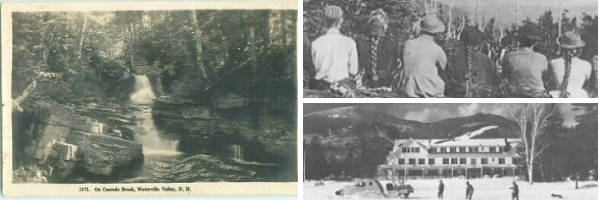

As the birthplace of freestyle skiing and a mountain rich in alpine history, Waterville Valley is well known for its skiing. However, long before the ski trails were cut it was a premier hiking destination. In the 1850s, entrepreneurial innkeeper Nathaniel Greeley oversaw the development of what historians Laura and Guy Waterman call "the Northeast's first trail system" in their book Forest and Crag. Greeley was among the earliest settlers arriving into the Valley in 1830 where he built a cabin and began acquiring and clearing land, eventually more than 1,000 acres.

On July 1st, 1860, Greeley and his two sons opened a three-story hotel to bring more travelers to the Valley and in that same year, he created two long distance bridle paths connecting Waterville Valley to other White Mountain resort areas. One path led to Greeley Ponds and onto the Sawyer River Valleys and the Saco Valley where visitors could access Crawford Notch. Many people would take this route by horseback to reach the top of Mt. Washington in just a day's time. In fact, there used to be a sign at the junction to the Waterville Flume that read "Mt. Washington 28 miles." The second bridle path that Greeley opened connected Waterville Valley to the south side of the Sandwich Range by creating a trail that lead over Mt. Tripyramid and Flat Mountain and up to the Whiteface Intervale. Shortly after he developed a third path through Thornton Gap connecting Waterville Valley to North Woodstock.

Greeley wasn't just connecting paths to other resort towns, he also had the goal of enhancing outdoor recreation in Waterville Valley by building trails to several peaks around the Valley, including Mt. Tecumseh, Mt. Osceola, Sandwich Dome, and Welch & Dickey Mountains. He built trails to natural features that are now popular hiking destinations, including Greeley Ponds and the Waterville Cascades. In 1888, a group of hotel summer guests formed a volunteer group known as the Waterville Athletic Improvement Association (WAIA) to "manage the recreational activities of the Waterville Valley, and to encourage all healthful exercise and afford facilities thereto." One of the group's primary functions was to build and maintain hiking trails, along with footbridges and shelters. With the new group in place, in 1890, the Waterville Valley trail network was expanded with the new trails to Kettles, the Scaur, the Boulder, Davis Boulders, and Goodrich Rock.

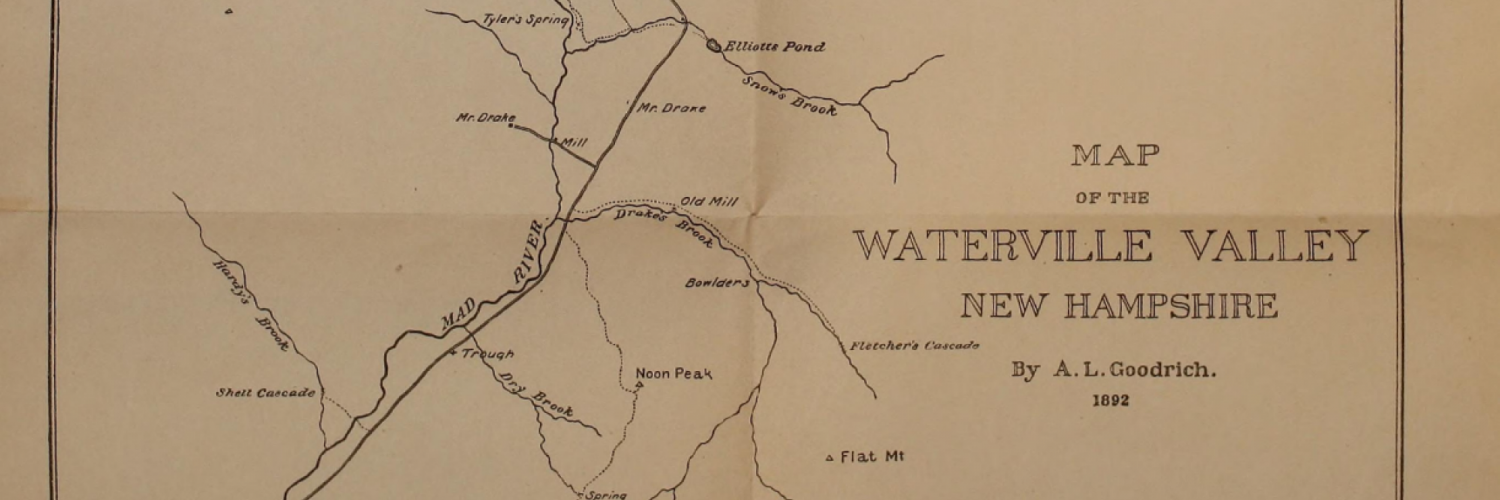

Although some of Greeley's paths were later replaced by new trails, and others fell into disuse, many of his routes are still traveled today and he created a well-established tradition of hiking in Waterville Valley. In the summer of 1879, the AMC members and Waterville Valley seasonal resident, Arthur Goodrich continued on his tradition by building new trail routes up Mt. Tecumseh and Sandwich Dome (today's Sandwich Mountain Trail). The AMC also opened the Livermore Trail as a through route to the Saco Valley via Livermore Pass, replacing Greeley's bridle path through Mad River Notch.

Goodrich later blazed the trails to the Kettles and the Scaur around 1890, and he was the discoverer of the huge glacial erratic that was subsequently named Goodrich Rock. In 1900 he opened a rugged route up the ravine of Osceola Brook to Mt. Osceola. In the early 1900s, Goodrich laid out several new trails in Waterville Valley, including paths to K1 and K2 cliffs on Mt. Kancamagus, Flume Trail, and a now abandoned footpath that led to the town of Sandwich via Cascade Brook which is now known as "Lost Pass."

Goodrich can be considered Waterville Valley's "greatest hiker" and he also cultivated a long-standing tradition in New Hampshire. He was the founder of the now popular activity known as "peak bagging" in the White Mountains. In 1931 he published an article in Appalachia, the journal of the AMC, which proposed a list of 36 White Mountain 4000-footers that he had climbed, with the stipulation that each peak must rise at least 300 feet above any ridge connecting it with a higher 4000-foot neighbor. In 1957, the AMC formally created the NH48 list using the 200-foot rule. Five of the peaks on this popular list are part of Waterville Valley (Tecumseh, Osceola, East Osceola, Mt. Tripyramid, North Tripyramid), and two more (Whiteface and Passaconaway) are within the town's boundary.

Over the years the White Mountain National Forest has taken over maintenance of many of Waterville Valley's 125 miles of hiking trails with the help of the Waterville Valley Athletic & Improvement Association (WVAIA) who maintains approximately 24 miles of trails. Thanks to the WMNF, the WVAIA, and other volunteers, the 160-year hiking tradition of Waterville Valley is alive and thriving today.

About the Author

Stacie has been skiing in the Northeast since she was 4 years old and has been working in the ski industry for the past two seasons at Sunday River and Sugarloaf. Stacie is now the Communications Manager for Waterville Valley Resort and resides in Plymouth. When she's not skiing you can find her hiking in the White Mountain, climbing, or relaxing by a lake or river.